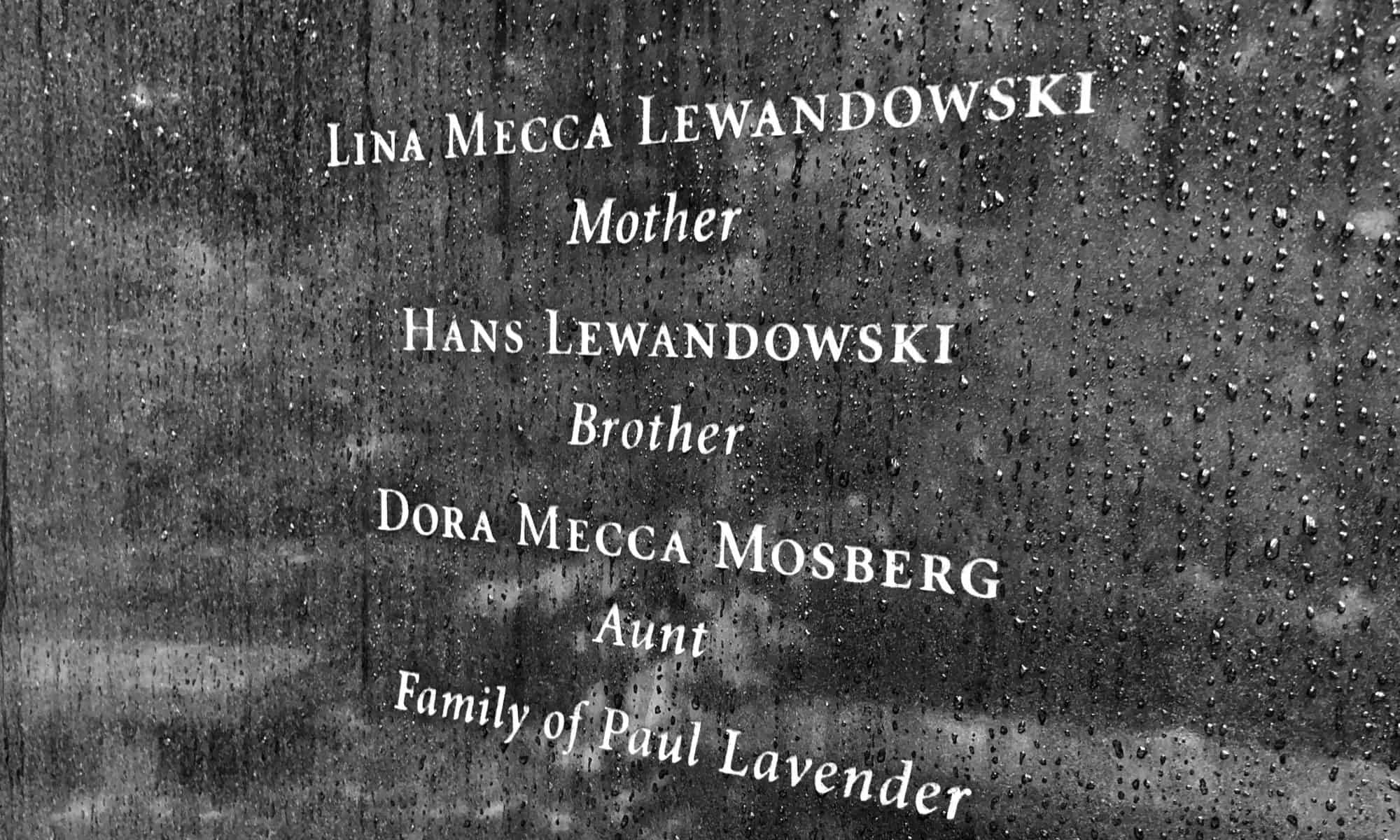

Paul Walter Lavender (born Lewandowski) was born on February 10, 1911 in Kassel, Germany. His parents, Jacob and Lina Lewandowski had three other children: Herbert, Irma, and Paul’s fraternal twin brother, Hans. His sister died when he was five years old, and his father died in 1936. Paul’s mother and his brother, Hans, died in the Holocaust – one in Auschwitz, one in Sobibor. His older brother, Herbert, fled first to Holland, then France, and eventually to Switzerland where he spent the rest of his life with his family.

In 1933, when Paul was 22 years old, he was fired from his job as a glass, china, and housewares buyer for a department store in Koblenz, Germany. Fleeing growing antisemitism in Germany, he fled to Holland. There he became a peddler of coffee and tea, selling groceries door to door from a cart, mostly to other German refugees.

Tap the grey bar and listen to Paul talk about the fate of his mother and brother.

Interviewer: What did you hear about the rise of the Nazis, while you were in Amsterdam?

LAVENDER: That’s a very good question because even there we heard over the radio the speeches of Hitler, day and night, screaming. We saw young boys with armbands with the swastika. In other words, there again, I had the feeling this is not the place. I felt it was much too close to Germany. So I said to my mother and brother, “I want to go to America.” They said, “What for? We’re here, safe here in Holland.” I said, “I don’t feel safe.” Naturally I didn’t know that Germany would invade Holland, but still there was that feeling of not trusting the situation. So I went while my brother and mother stayed, unfortunately.

Read and listen to Paul’s full interview here.